There are places that impress through excess.

The Douro is not one of them.

The Douro convinces through structure.

Wine.

Land.

Food.

Remove one, and the others lose their meaning.

We left Porto immediately after landing from New York. No decompression. No buffer. The old train did the work for us. Metal, oil, age. It smelled like Europe before Europe decided to explain itself to visitors. There was something faintly unruly about it- like a relic from a time when movement still carried risk.

Once the tracks began to follow the river, the valley revealed its logic. The Douro does not open theatrically. It asserts itself slowly, through repetition: slope after slope, terrace after terrace, schist exposed like bone. The river snakes not out of laziness, but necessity. Every curve feels load-bearing. Thrilling.

This is not scenery.

It is infrastructure.

Structure is a misunderstood word in wine.

People confuse it with power. Or density. Or alcohol.

They are wrong.

Structure is composure under pressure.

Tannins that hold without gripping.

Acidity that lifts without cutting.

Alcohol present, never leading.

Fruit restrained enough to age, not perform.

The Douro, at its best, understands this instinctively—because the land itself imposes it. Heat is real. Sun is relentless. Schist is unforgiving. Anything unbalanced here collapses quickly.

We stayed at Quinta de São Luiz, perched above the river with the quiet authority of a place that doesn’t need to prove anything. Old vines. Vertical hills. Paths that punish laziness. Larry climbed to the peaks, the after the rest of us followed gravity downhill to the river’s edge and paid for it on the way back up.

In the mornings and late afternoon, the infinity pool wasn’t indulgence- it was calibration. Cold water. Sharp light. No softness yet. Afternoons were earned.

The first dinner mattered.

Mackerel crudo.

A dangerous dish if handled casually.

Oil without salt is flab.

Salt without acid is noise.

This worked because the structure held: salt sharpened the fat, acidity lifted without puncturing, texture remained intact. Paired with a restrained Kopke white blend, low in alcohol and high in line, the dish stayed vertical. Nothing sagged.

That’s when the trip revealed itself.

Pinhão is touristy. It always will be. But geography doesn’t care about crowds. The river still frames the town. The slopes still dictate behavior.

At Quinta do Bonfim, Pedro Lemos cooks with bilingual fluency-modern and traditional, without apology to either.

Frank’s cod came first. Modern in approach, but disciplined. Flake separated from oil. Salt placed with intention. Acidity introduced surgically.

I had the cabrito. No reinterpretation- I was surprised. The server spoke explicitly- No irony in the dish. Fire, time, fat, potatoes. The dish did exactly what it was supposed to do and nothing more. Amazing.

The same wine carried both plates- Quinta do Vesuvio 2020- not because it was neutral, but because it was structured. Firm tannins. Controlled fruit. Alcohol integrated, not declared. This is the Douro when it resists theatrics.

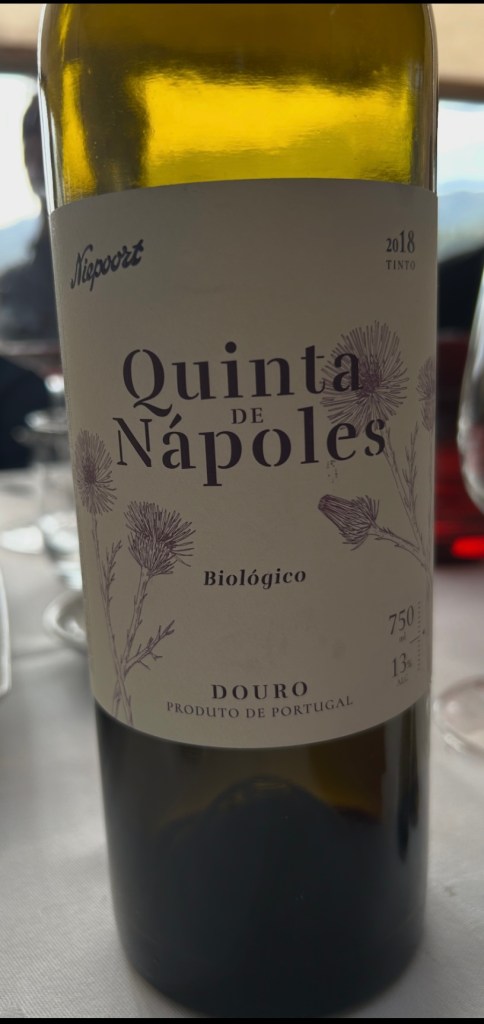

At Quinta dos Nápoles, along a tributary away from spectacle, the conversation turned technical. Fermentation. Alcohol management. Organic farming not as ideology, but as control.

Pedro, our host, didn’t flinch under detailed questions. Engineers ask differently. They look for stress points. The answers held.

The food matched the philosophy.

Farinheira that understood salt as foundation, not seasoning.

A vegetable soup where sweetness never escaped discipline.

Roasted baby lamb built on protein, fat, and patience.

The 2018 Biológico stood out—not for weight, but restraint. Thirteen percent alcohol. Fine tannins. Acidity intact. This was finesse achieved by subtraction. A reminder that the Douro does not need excess to be serious.

Rui Paula’s DOC was the apex.

Nine moments. Not courses—moments. Because structure isn’t linear; it’s relational.

Raw gave way to cured.

Cured to cooked.

Fat followed by acid.

Salinity by bitterness.

Sweetness delayed until it could be controlled.

Textures led. Flavors followed.

Grouper with Horseradish and Lime Kaffir where gelatin met tension.

The Crayfish Gaspacho with Melon built on salinity rather than garnish.

Wagyu beef with Black Bean Sauce was reduced, not weighted.

And the Douro Boyz’s favorite dessert- Cauliflower Ice Cream with Olive Crumble and Citrus oil- structured around contrast, not sugar.

Each wine framed rather than dominated. The most terroir intense wines were the SOL Alvarinho Quinta de Santiago & Mira do O, 2022 and Mirabilis Grande Reserva , Quinta Nova de Nossa Senhora, 2015. The Douro here acted as architecture, not decoration.

The lesson was consistent.

The Douro rewards discipline.

It punishes indulgence.

It remembers imbalance.

Wine, land, and food here share the same demand: composure under pressure.

The Douro Boyz- Larry, me, Frank and Hugo- didn’t just move upriver.

We moved deeper into structure itself.

And structure, once seen clearly, is impossible to forget.

Renato da Silva, NEUwine

The Old World Whites

The Old World Whites The West Coast Reds

The West Coast Reds